- Home

- Deb Olin Unferth

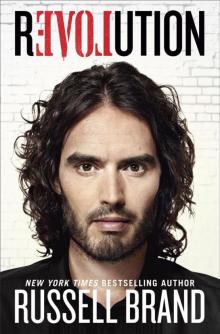

Revolution

Revolution Read online

For Comrade Robert Unferth

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Part One: The New World

McDonald’s

Popular Priest

Long Year For War

Send-Off

Part Two: Civil War

Bodies

Typical Man

Spanish

Job

Projects

The Evangelicals

Hermana Mana

Oh Brother

On the Road

Love

Visitors

Broken City

Wonderful Time

Good Ideas

Engaged

Parade

Heaven

Clean

Part Three: Internacionalista

Sarah’s

Sandalista

Chart Day

Feminism

Doctors

Bicicletas Sí, Bombas No

Nervous

More or Less, 2001

Part Four: Sick of the Revolution

Tiresome

Black Market

To Bluefields

Capitalism

Paradise

Fever

What I Remember of Panama

Sixty Bucks

Early Writings

Water

Censorship

Peanut Butter

Smaller

Forgettable Moments

What Happened to George

Part Five: Common Human Fates

Stuff

Sandino in the Sky

Where the Danes Stayed

Three Boats

Good Sport

In the Movie of Your Life

Fathers

Proposals

The Last We Saw of George

Part Six: Big Country

Private Eye

Another Ending

Final Robbery

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by Deb Olin Unferth

Copyright

PART ONE

THE NEW WORLD

MCDONALD’S

I had food in my heart and mind that morning. My parents had said they’d pick George and me up at the border and take us anywhere we wanted to eat. I wanted to go to McDonald’s. My father thought that was funny. Part of his story for a long time was how the first place I wanted to go when I came back from fomenting the Communist revolution was McDonald’s. Hey, to me at that moment, McDonald’s looked pretty good. We’d seen McDonald’s in Mexico, of course, and Honduras and other places, but we hadn’t been able to afford it. Now, approaching the border, I was thinking about that lighted menu board. I was thinking about how I already knew what the food I ordered would look like. I knew what the French fries would look like, what the containers would look like, although I’d never been to that particular McDonald’s. I knew what I’d get when I got a sundae. That seemed like a neat and attractive trick to me now. There would be toilet paper in the bathrooms. And soap. There were the little songs on TV, the McDonald’s songs that people all over the world knew and I had sung when I was a kid, the Big Mac chant, the Hamburglar. George was asleep beside me, had slept through the last seven hours of desert. “George, wake up,” I said. “We’re going to McDonald’s.”

POPULAR PRIEST

My boyfriend and I went to join the revolution.

We couldn’t find the first revolution.

The second revolution hired us on and then let us go.

We went to the other revolutions in the area—there were several—but every one we came to let us hang around for a few weeks and then made us leave.

We ran out of money and at last we came home.

I was eighteen. That’s the whole story.

* * *

George and I were walking through a shantytown. Two weeks into Mexico, the beginning of our trip, and we were outside Mexico City. An American priest walked ahead. He was saying hello to people and taking their hands. He was saying good-bye to them and waving. Que te vaya bien. Adiós. Dios te bendiga. They chimed back. We walked a long way, following this priest.

It was 1987, and at that time these little liberation theology institutes were set up all over Latin America, “popular churches,” they were called, short chapels with small gardens, places for people to get together and help usher in the revolution. The priests were in charge and they could be from anywhere—South America, Spain, the States—but most were from down the street. We liked to drop in when we found these setups. We interviewed whoever happened to be hanging around and we borrowed books from their shelves and got the people to take us out. We liked to get the scoop.

So we’d met this priest at his instituto and he’d brought us to the shantytown. He was doing some work, fixing up some floors. He thought we just might like to see.

When you think of a shantytown, you imagine a few square blocks of board and tin, some chickens running through, but it’s a whole city, a thousand thin paths, kilometers and kilometers of housewives standing outside askew miniature-sized houses, not a window pane in sight, the air moist and buzzing.

“These people are born and die here,” the priest was telling us. “They have no way to get out.” He raised his hand to show us where they had to stay.

“Well, at least they’ve got their little houses,” I said. I was impressed with how tidy it all was. “Some have less than that.”

The priest looked over at me.

Then he was gone. Just like that. Left George and me standing by a flower of electrical cords coming out of a pole.

We waited a while. Roosters called to each other in the distance. Then we started puzzling around the shacks, trying to find our way back. We were soon lost. We felt stupid and rude walking along, a couple of idiot gringos slapping at the mosquitoes and grinning. We were sad about the priest. Why had he gone away? He’d left us and we deserved it. We’d been bad-mannered. I’d been bad-mannered, according to George. George knew better than to say a thing like that. Oh yeah? I said. Then why had the priest left George here with me?

These priests for the liberation. You did not want to mess with them. Latin America was swinging to the left, hoisted on pulleys by these radical priests, and some said the Vatican was to blame. In 1962 the pope had summoned the world’s bishops to Rome for the Vatican Two Council, to talk about how to renew the Church, how to be relevant to the laypeople. The story goes that the bishops met each fall for four years. They talked about things like how perhaps they should not say mass in Latin anymore because no one understood it (although the entire conference took place in Latin). Some of the South American bishops and priests thought that one way to renew the Church was to organize the lay into groups, maybe even guerrilla armies, and then rise up and overthrow their governments. Soon a continent of priests was storing weapons and reading Marx in the name of Vatican Two. They turned their churches into revolutionary enclaves and invited students to come live in them like a herd of hippies. Some priests held secret meetings with guerrilla rebels. Some manned radio frequencies that kept tabs on the national guard. And when the skirmishes began, some priests came out shooting. Every day their chapels filled with citizens, and the priests never stopped talking about Vatican Two, the theology of liberation, how the Church was a socialist soldier for the poor, and how grateful they were for this mandate from God. Of course the pope didn’t mean to produce an infantry of gun-touting South American priests, and he said so, but it was too late.

* * *

Late for the pope, but early for George and me. This priest was the first of his kind, we’d found. We walked, lost, through the shantytown. Houses tacked up to each other with clothes hangers, a c

obweb of roofs held down with tires. Outhouses winged out over the river. Lightless rooms, cardboard town. We began getting upset at seeing how poor the people were, now that we were looking more carefully. Ladies and kids stopped us and pointed in different directions, laughing behind their hands. A few folks followed us. We handed out all of our bills. We didn’t see how we would ever find our way back. George was taking us in circles. Oh, right, he said, he was taking us in circles, perfect. We began to panic.

Suddenly the priest was there, stepped out in front of us. Ho ho. He’d stopped in to look at a floor he and some friends had put in. Lost track of us.

What, had we been nervous about getting stuck here? he wondered. About not being able to get out?

“Okay, okay, we get it already,” we said, though we did not.

LONG YEAR FOR WAR

We had wanted to go to Cuba, but we didn’t know how to get there. George and I had very little money and we weren’t resourceful, and it was illegal to go, which was awkward. Besides, there was no action there anymore. Just parades and congratulations and prisoners. Nicaragua had a very good revolution too. They’d won their revolution, for one thing, and they were in the papers all the time, and we could ride the bus there. They also had Russians.

The other revolutions—in El Salvador and Panama, in Guatemala, in Honduras—weren’t revolutions proper, more like civil wars, military coups, and armed uprisings. They straggled along with their broken tanks and their camps in the jungle. We believed their revolutions were on the way.

Nineteen eighty-seven was a big year for war in Central America. Still, it took George and me a while to find any. We rode through Mexico on bus rides that lasted eighteen hours, twenty-two hours, twenty-six hours. We passed through Guatemala, where we had to fight our way through the tourists just to see a little scrap of the land. The tourists crowded together like shrubs, trying not to get knocked over. Mostly in Guatemala we were herded by heavily armed soldiers along a well-worn track that took us from pretty spot to pretty spot (look at the Indians! buy their amusing costumes to take home for yourself! ride a wooden boat across a glassy lake!).

People didn’t have the details on Guatemala yet. We heard about the killings but we didn’t know the extent and the scale. Or maybe we did know and chose not to understand. A couple of years later, when we began to hear so much about the death squads, the scorched earth policy, the tens of thousands of dead, the tens of thousands fleeing the country, I had a sick feeling of knowledge. A massacre, an exodus, going on all around us, had been for years, and still going on after we’d gone, and we saw none of it. We saw a few tattered labor protests, Indians sitting on cardboard in the plaza. Mostly we saw soldiers. Soldiers were in all the shops and banks, on the buses and in the cafés. There were pageants of them on the street. They stopped taxis and leaned in the windows. “Papeles,” they said every minute or two. They held machine guns and wore camouflage uniforms, high black boots, helmets, strings of bullets across their chests. On their belts they carried clubs, pistols, Mace, hand grenades.

They were small and young and cute, like toy soldiers. Many only came up to my mouth. They stood and looked at us in moody silence. Poked at the pages of my passport. Sometimes they would pose for a picture.

* * *

In those days the Guatemalans still thought they owned Belize or thought they owned it more than they think they own it now, so many of us secretly felt that Belize didn’t count. In any case Belize didn’t have a revolution. But we went to have a look.

These were the days before the Peace Corps had been let back into the country. The days before Belize had even kicked the Peace Corps out. These were the original Peace Corps days, the days that led to their expulsion from Belize. They were all over the place, the Peace Corps volunteers, drunk in hammocks, lying on the sidewalks. “Hang on, man,” they called to us. “Want a smoke?” George and I picked our steps over them on the way to the bus station.

* * *

Our main ambition was to help the revolution. George and I wanted jobs, what we called “revolution jobs,” but it turned out that few people wanted to hire us and if they did, they almost immediately fired us.

But he and I also conducted interviews. This was his idea, and he was in charge. We started in Mexico and interviewed people clear down to the Panama Canal, dozens of people—politicians, priests, organizers. We brought a bagful of tapes with rock music on them and recorded over the tapes one by one with a handheld cassette tape recorder. Some people gave us only twenty minutes—the press secretary of Guatemala (with his fake, thin clown smile), the minister of culture of Nicaragua (who wore a beret indoors). The strays—the artist, the small-town priest, the local Native American—would talk for hours if we let them (if George let them). In Nicaragua everyone wanted to be interviewed, top people in the government and church. The taxi drivers wanted to be interviewed. The kids wanted to be interviewed. Their fathers wanted to be interviewed. In Bluefields, Nicaragua, we interviewed the mayor of the city, the leader of the Miskito tribe, the soldiers who had provided military escort to that part of the country. In El Salvador no one wanted to be interviewed. We got only four interviews—one with a painter, a few with some priests—but no one in the government would talk to us or even look at us. We went to the Casa Presidencial in San Salvador every day for weeks and couldn’t get near the place. The guards told us that the entire government was on vacation. Every day they told us this. “Still on vacation,” they said, spreading their hands. “¿Lo crees? Can you believe it?”

“No, I cannot believe that,” said George.

* * *

I don’t know what happened to all those tapes. When we came back to the States, we had them first in plastic bags on the floor by the door of our apartment. Later I recall them sitting in a couple of broken boxes. After that, I’m not sure. Neither of us ever listened to them again, as far as I know.

SEND-OFF

I knew my mother and father were not going to let me join the revolution, so I didn’t tell them. I sent them a letter from Mexico. I wrote the letter in Nogales on the American side of the border, then I crossed the border so I could mail it from the Nogales post office on the Mexican side. The letter was short and went something like:

Dear Mom and Dad,

I am writing you from Mexico. I’m sorry to tell you in this way, but I’ve left school and am going to help foment the revolution. I am a Christian now and I have been called by God. Due to the layout of the land, we are taking the bus.

My father still talks about it. “She told us nothing,” he says. “We had no idea. I open the mailbox and there’s a letter from Mexico saying she’s off to foment the revolution.”

He’s been telling it the same way all these years. He used to shout it, “My own daughter told me nothing!” and point at me—there she is, the traitor, the nutcase, the smartass.

Later he said it sadly, shaking his head: “I had no idea.”

Even later he said it with pride. His loony girl, a bit like him. Do you know he once owned a Communist bookstore?

Now he tells it like an old joke. “So one day I open the mailbox…”

* * *

Before we left, George brought the stuff we would need up out of his parents’ basement—backpacks, insect repellent, flashlights, soap, some philosophical books about the Bible. I threw my other belongings away and I did it happily because at the revolution I would need only what I could carry. We put our money together (we each had a thousand dollars). We got shots and a bottle of malaria pills.

George told his mother our plan. We sat at her kitchen table while he explained. She listened and then took out some pot holders for us to take along and bookmarks with pictures of God on them. She had the face of captive royalty, the voice of something gentle in a cage. She told me to memorize the Bible bit by bit and then to write it down at the revolution and send it to her in the mail. We left the pot holders behind, but she also gave us a very large, very heavy canister of vitami

n powder that we never used but carried for months and months over borders, on boats, through storms.

George’s father was there too that day but he didn’t speak. I never saw him speak, in fact, and it seemed to me that no one had. The man sat looking angry, alone on the sofa in the living room. He rose only to come through the kitchen on his way to the door.

* * *

The year George and I went was nearly the end of the revolution, but the way it looked to us, we were arriving at the very beginning. A new world order. Everybody in the world was talking about the revolution, how it was coming over the ocean, it was floating up through Texas. It would spread over America. People were writing their ideas in the papers. But two years later the Berlin Wall came down and soon after that the Sandinistas were gone, the Cold War was over, and the guerrillas in El Salvador handed in their arms, put down their names on a peace accord. By the time we arrived, the Communist decay had set in, but we didn’t know. There were a lot of people like us on the scene.

PART TWO

CIVIL WAR

BODIES

George and I were on a bus headed into El Salvador, a secret bus in the middle of the night. Soft bundles of people sat on each seat, but the space was so voiceless and dim, you’d think we were all gone and the bus rode emptily along. And yet the bus was heavy, pulling itself up hills around bends. You could feel the brakes holding back the weight as we coasted down. I was angry with George. “This is not going to work,” I told him. Dark windows, the weird sound of cicadas. An occasional wet branch hit the glass. George said nothing.

The bus shuddered through a downshift and rolled to a stop. We’d run only a few kilometers over the border so far. The people in the seats around us began murmuring and shifting at the windows because out on the road we could see men with machine guns filed out in front of the bus and walking along the sides.

* * *

Barn 8

Barn 8 Revolution

Revolution Wait Till You See Me Dance

Wait Till You See Me Dance